Recently my son asked me about a tin of salve that his Grandmother Rosser once used. He remembered the distinct blue colors and lettering and had noticed the same kind of container on a display in an antique mall.

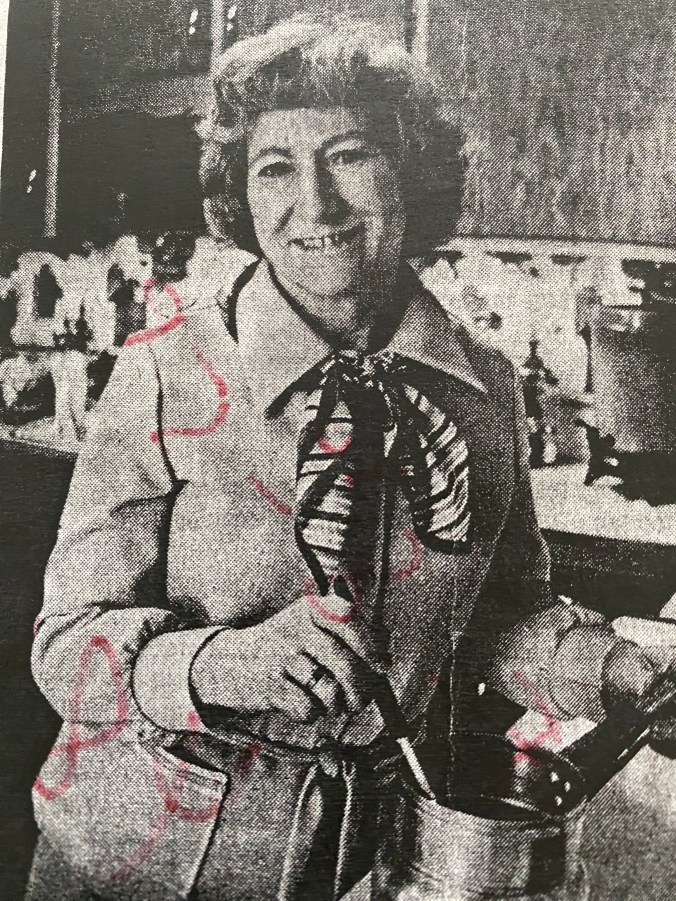

“Yes, that was the miracle drug Medicated Ointment that she’d once sold as a Rawleigh products dealer,” I told him. Then I shared some of the ‘backstory’ of Mama as a business woman. Her story and mine were intricately woven together from my point of view.

Growing up in the South, during the turbulent sixties, I had experiences interacting with Black people. Our neighborhoods were segregated with the Black section of town, known to White people as “Colored Town.” I lived in the country so the rural area had houses of White people and Black people scattered throughout.

As a farm girl, some of my earliest memories of the two races being together was when we were working in the tobacco harvest. My father hired Black and White men and women to help–the men in the fields and women at the barn. Those July days, things came to life with the influx of helpers to ‘put in that barn.’ It would take most of the day to fill it with the green leaves of that cash crop that hung on wooden sticks and cured above the oil burners. Before I was old enough to hand the tobacco–I played near the trailer of stacked leaves and listened in on their conversations.

What was unique for me was my experience with my mother’s sales business. Mama sold Rawleigh household products door-to-door in “Colored Town.” She and her sister, Inez had gotten into working for that company through their Uncle Jones–who’d done that for years.

Mama worked her route every Saturday when the woman of the house was home. She’d pack our car with the orders of mops, chenille bedspreads, flavorings, liniment, “Pleasant Relief,” medicated ointment, hot irons and hair products; those are the ones that are most vivid in my memory.

When I wasn’t needed for chores at home, I would go with Mama on the route. As a young girl, I was fascinated by being inside the homes in that part of town. If there were no children in the family, I had to sit quietly while Mama did her transaction, talking with the women, writing out a receipt in her little book with the carbon paper, then placing the bills and change in her money pouch.

I never told any of my friends about my trips into Colored Town; what would they think of me, of Mama, that we were in that ‘part of town’ every Saturday? If my friends came to my house and we went into our smoke house–where years before they’d cured hams from the farm, they would have seen Mama’s boxes of Rawleigh products. If they fell down when we were playing and had a skinned knee, Mama would have cleaned it and then slathered on the ‘miracle drug’ Medicated Ointment; it would cure anything.

I carried those memories of Saturdays for years and then eventually wrote some stories related to those childhood experiences. I didn’t appreciate Mama’s role as a sales woman until I had a chance meeting with a fellow writer at the Weymouth Center in Southern Pines. There, I was one of the writers in residence for a week, along with a Black woman–who was a jazz singer as well as a writer. We would talk over coffee each morning before diving into our individual projects. One evening, we sat in the living room and talked about our childhood–how we started writing. She was from rural, eastern North Carolina and lived at a distance from town. Somehow, the conversation wound around to me going with Mama on her Saturday route.

She looked at me, her eyes with a sudden realization, then a smile spread across her face.

“Your mama was The Rawleigh Lady?”

Her response surprised me, her voice filled with warmth.

“Yes,” I responded. “She had that route for many years.”

She had a faraway look in her eyes, like a film from yesterday was projecting inside her mind’s eye.

“Oh how my mama, and the other women in our neighborhood, loved the Rawleigh Lady. She would come when the men were away at work–so the women could shop freely,” she said, and then chuckled. “Back then, they couldn’t do that at the stores in town. The shop owners would be watching them, assuming they were going to steal.”

I listened to her, fascinated by her point of view, by her perspective of my mother and others who’d sold those products door-to-door. I’d never considered why it would be hard for Black people to shop in town–like White people, with no worries that they were being watched.

That conversation opened a door for me. I saw how my mother’s business had not only provided needed money for our family but also a service for her Black customers. I’d admired how Mama went, unafraid into those neighborhoods when we were having racial unrest. I’ll always remember one of her customers warning her, “Mrs. Rosser you be sure to get out of this neighborhood before dark.”

Now, I’m glad to tell my son about his grandmother’s entrepreneurial venture at that point in history. It occurs to me in the unrest of this time, it would be wonderful if we could have conversations with other groups of people who are different from us in race, ethnicities, or politics. How we need a better understanding of each person’s unique point of view.

With love and dedication to The Rawleigh Lady.

Very nicely written Connie. I really enjoyed it. Big SisSent from my iPad

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Harriet.

We shared such an interesting time with a multifaceted mother.

Best to you,

Connie

LikeLike

Fascinating story Connie!

Get Outlook for Androidhttps://aka.ms/AAb9ysg

LikeLike

Thanks so much for reading and commenting. Best to you!

LikeLike

Super!Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Ted. I always appreciate your enthusiastic support. Best to you!

LikeLike

Connie, thank you for sharing this beautiful, layered memory. Your mother’s work was a bridge in hard times, and your storytelling brings that legacy alive. Marie Ennis O’Connor

LikeLike

Thanks so much for reading and for your compliment, Marie. I like how you say Mama’s work was a “bridge.” I hadn’t thought of it that way but you’re right.

Best to you!

Connie

LikeLike